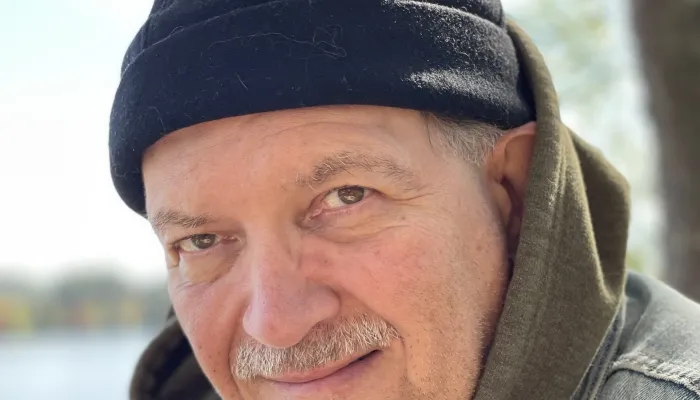

Canisia Lubrin

Biography

Canisia Lubrin is a writer, editor, teacher and critic, with work published widely in North America, as well as in the U.K.. Translations of her work include into Spanish and Italian. She is the author of the awards-nominated poetry collection Voodoo Hypothesis (Wolsak & Wynn) and augur (Gap Riot Press) finalist for the 2018 bpNichol Chapbook Award. Lubrin's fiction is anthologized in The Unpublished City: Volume I, finalist for the 2018 Toronto Book Award. She teaches English at Humber College and Creative Writing at Sheridan College and in the University of Toronto's School of Continuing Studies.

Micro-interview

I don’t remember reading any particular poems when I was a teenager. We studied very little poetry in high school and the fact that I don’t remember any of them is very telling. I think this may be due to some strange amnesia or to splitting my time, impossibly, among every high school club or to the poems themselves having zero resonance. But I knew that I regarded poetry with intense reverence.

I wrote songs as a teenager, which I considered poetry — music is the anatomy of poetry. I wrote my first serious poem in 2008 in my undergraduate Intro to Creative Writing class. I struggled for many years to view myself as a poet even though I always suspected there to be a poet in me somewhere.I thought poetry something close to the Gods, a thing that I could read and enjoy but never write. Am I ever glad I scaled that wall.

I wonder if this question has always been a hard one to answer: we have real trouble naming things we cannot measure. I think that today a poet writes into and out of the chaos of life the things that trouble notions of humanity as a species with only utilitarian interests or provocations or purposes. Just yesterday I heard a college teacher saying that he doesn’t support people choosing an art as a career, that he would easily donate to an organization raising funds for, say, a carpenter’s association but would never give his money to the ballet. It is a wonder, then, why it is easy to conceive of architecture with no consideration for what architecture owes to the artist. Perhaps, ultimately, the poet’s job is as the poet decides, but the work of poetry is elemental and expands the possibility for our lives beyond mere utility, beyond the basic needs that reduce us to some oversimplified version of “what is real and who we are.” I would hate to live in a world devoid of art.

I wrote this poem [“Sons of Orion”] after the murder of Philando Castille. It came out of grief, anger, and an inability to turn away. It came from having to face anew the world that exists and might await my own black-bodied children.

from thirsty by Dionne Brand